Explainer: The link between poverty and homelessness

October 17 2017

By guest blogger Violet Kolar, Researcher, Launch Housing

For the past 25 years Australia has enjoyed uninterrupted economic growth, yet in 2016, 3 million people in Australia were living below the poverty line after paying for their housing, including more than 731,000 children under the age of 15.

According to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA), poverty remains persistent and entrenched for an estimated four to six per cent of Australians. This means that up to 1.5 million people live their day-to-day life in a chronic cycle of relentless hardship and long-term deprivation.

So what is poverty, and what is the link between poverty and homelessness?

What is poverty?

Poverty is about financial disadvantage; it means not being able to afford the basic necessities of life that would provide a minimum standard of living. Not having enough money also makes it extremely difficult to be able to participate as a member of the community, whether in education or training, in paid work or socially.

Poverty also has a profound impact on a person’s health and wellbeing. A strong body of evidence highlights poverty as a key influence for adverse outcomes in children’s health and wellbeing in their first 1,000 days. A widely used measure of poverty uses the median income level to calculate the poverty line for different household groups. As a relative measure of financial disadvantage, the poverty line is updated regularly, but is generally set at 50% of median income.

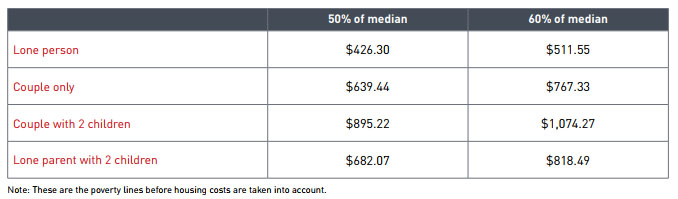

In its 2016 report, Australian Council of Social Service and Social Policy Research Centre (ACOSS) estimated four different poverty lines based on the 50% or 60% of medium income and whether housing costs are excluded or included. Table 1, for example, shows that at 50% of the median income in Australia, the poverty line for a single adult was $426.30 per week. For a couple with two children, the 50% poverty line was $895.22, while for a lone parent with two children, it was $682.07.

Table 1: Poverty lines by family type, 2013-14 (Income per week after tax, including social security payments)

ACOSS found that more single parent families (33.2%) experience poverty than couple families (11.3%). In fact, the poverty rate for children in single parent families was more than three times the rate for children in couple families.

The majority of people living below the poverty line received social security as their main source of income.

While social security payments are meant to provide a social safety net, levels have not kept pace with the rising cost of living resulting in payments falling well below the poverty line. A recent report by researchers from the University of New South Wales showed a gap of between $46 and $126 per week for households on income support.

This means that individuals and families struggle day-to-day to afford even the most essential things like food, being able to pay bills, or being able to secure and maintain housing; leaving households especially vulnerable to homelessness.

How are poverty and homelessness linked?

Homelessness is one of the most extreme manifestation of poverty. There is both national and international evidence that highlights the link between poverty and homelessness.

A number of Australian studies (here and McCaughey, J. (1992). Where Now? Homeless Families in the 1990s (Policy Background Paper No. 8), Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne) have also reported on the families’ entrenched financial hardship and therefore their ongoing risk of homelessness. This was consistent with a 2013 collaborative study by Swinburne researchers that showed families still remained vulnerable even when housing had been secured.

Figures from the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection show that 105,287 Victorians received assistance from a homelessness agency during 2015-16. The top three reasons for seeking assistance were: domestic and family violence, financial difficulties, and housing crisis. A total of 45,752 clients had a need for accommodation, with the remaining clients needing support to keep their accommodation.

Food and utilities

Table 2 below shows the weekly breakdown of expenses for a single parent with three children on income support of $820 (includes rent assistance and benefits). As you can see, despite Income Support, Family Tax Benefit and Rent Assistance income – this amount leaves the family living below the benchmark poverty line by $15, with no savings if anything goes wrong.

| Income | Expenses | ||

| Income support and Family tax benefit | $733 | Rent | $340 approx |

| Rent Assistance | $87 | Groceries | $200 approx |

| Bills (electricity, gas, mobile phone, internet) | $60 approx | ||

| Clothing and footwear | $30 approx | ||

| Health | $20 approx | ||

| Personal care | $25 approx | ||

| Education | $45 approx | ||

| Transport | $100 approx | ||

| Total income | $820 | Total expenses | $820 |

| Poverty line for a single parent with three children | $835 | ||

| Difference | -$15 | Savings/emergency funds | $0 |

| Source: Estimated using Budget Standards developed by Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW | |||

Once rent ($340 for 3 bedroom dwelling) is deducted the family is left with $68 per day to cover the cost of groceries, transport, childcare, and bills. One survey found that individuals on income support were generally left with just $17 per day (after deducting rent) to cover the cost of food and utilities.

The weekly expenses for this family leaves them in constant financial stress with no money left over week by week; there is nothing to save and if there is an unexpected bill or health emergency, the family will be in trouble. Between 2009/10 and 2013/14 in Australia, disconnections due to financial difficulty had increased 136%; for those on hardship programs it was a staggering 202%.

Many are, therefore, turning to charities for help. In a 2016 study of hunger in Australia, Foodbank (the largest food relief organisation in Australia) found that 18% of Australians experienced food insecurity in the preceding 12 months, meaning that they did not have enough food to eat and could not afford to buy more. They also noted that more than 644,000 people (33% are children) access food relief from foodbank agencies each month; a 24% increase from 2014.

It is a brutal indictment of a prosperous Australia that so many of our fellow citizens simply do not have enough money to spend on food.

Lack of affordable housing1

The decline in affordable housing means that access to secure housing is increasingly difficult for low income households. The shortage of public housing has resulted in targeting those households in greatest need. Despite this, it still remains difficult to access. Figures show that more than 32,000 applicants were assessed as eligible for public housing in Victoria. Of these, 9,866 were prioritised for early housing but had to be put on a waitlist.

Affordable private rental housing has also become increasingly difficult. In June 2016, only 8% of all dwellings in metropolitan Melbourne were affordable. Further, for the same period, there were only 29 one-bedroom properties affordable to someone on the Newstart Allowance across all of metropolitan Melbourne.

In order to improve access to housing in the private rental market, Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) is available; however, it cannot guarantee that housing will be affordable. In 2015, 306,490 Victorian households received the CRA (14% of all households); the median entitlement was $124.50 per fortnight. Despite this financial assistance, 39% of households were paying more than 30% of their income on rent, which means they were experiencing housing stress. Based on analysis of the level of need, a report to Infrastructure Victoria estimated that “between 75,000 to 100,000 vulnerable low income households require better access to affordable housing”.

What needs to happen?

Launch Housing’s mission is to end homelessness; each year we support more than 18,000 people experiencing homelessness. Launch Housing delivers a broad range of housing and homelessness services across 14 Melbourne sites. This includes crisis accommodation; transitional housing; support for people experiencing homelessness; Education First Youth Foyers; and HomeGround Real Estate, one of Australia’s first not-for-project real estate agencies.

Launch Housing advocates strongly for change but efforts to end homelessness, and to address the persistent and entrenched hardship experienced by individuals and families, cannot be done by agencies alone. It requires government to develop policies that strengthen the social safety net and to expand the supply of social and affordable housing. It is critical to invest in prevention and early intervention strategies to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty to ensure that children are given every opportunity to grow up to be productive and participating members of the community.

1Affordable housing refers to when households in the bottom 40% of Australia’s income distribution pay less than 30% of their income on the cost of housing (rent or mortgage).